That Joke isn’t Funny Anymore! What now for Corbynite Laughter?

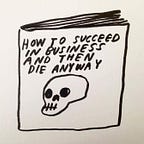

Satire and humour have been a steady and important presence throughout the rise, and also the fall, of Corbynism. The Left’s relationship to and engagement with political humour has provided a fascinating undercurrent to the political turbulence of the past five years — from the ecstatic incongruity of ‘Cans Corbynism’, in which the least likely of leaders, the Beta-male, the gardening grandad, was ironised as ‘the absolute boy’ at football stadiums and music festivals, to the relentless spamming of Keir Starmer’s social media profiles with ‘any other leader would be twenty points ahead’ or photoshopped anthropomorphised pork adorned with jingoistic union flags. It is difficult to imagine the social phenomenon of Corbynism shorn of the humour and satire that ghosted its turbulent trajectory, from acerbic tweets to lairy chants and novelty T-Shirts.

On the one hand this unshackled Corbyn and the Left from their decades-long reputation for dry humourlessness. On the other, it created inconsistencies and contradictions within the Left, particularly with regards to its desire to gatekeep the permissible limits of free speech which the Right has been able to exploit and incorporate into an ever-expanding culture-war which uses the exposure of hypocrisy as its ammunition.

These contradictions burst to the fore in the wake of the recent failed suicide bombing in Liverpool when Paul Nickerson, a Conservative Councillor, posted a crude photoshop of Jeremy Corbyn. Corbyn, holding a wreath of flowers, was walking up to the car used in the attack, still ablaze. It was captioned ‘unsurprisingly’ on the councillor’s Twitter page. The image sparked outrage among many on the Left, including nationally prominent journalists who called the image ‘vile’ and ‘pathetic’.

Some suggested that the subject material of the joke, both the attempted bombing and the historically contested allegations alluded to in the joke were ‘too serious’ to be subjected to such light treatment. Some felt that the gag was fine, but not befitting of somebody holding public office. Others felt it was simply not funny. News then emerged that Corbyn had successfully filed legal action against Nickerson, who posted a public apology on social media and has been ordered to pay substantial damages.

I do not begrudge those claiming that those who ‘play stupid games’ should ‘win stupid prizes’. However, I think it is important that the Left takes a moment to consider the implications this case may have on our own approaches to political humour before popping open the champagne. After all, the celebration of such litigious successes only further legitimises the fundamentally inegalitarian and unjust libel laws in this country which can just as easily be used to silence us, as Rachel Riley proved just days ago. We also should not forget that the Left has had a degree of success in using humour as a political tool to spread its redistributive and populist message in the face of a media class which has defamed Corbyn on a near daily basis for years. Unfortunately, this tool now feels like it is getting blunter by the day.

A joke’s content is revealed by the disparate fragments of pre-existing knowledge brought into its orbit, which are then instantaneously repositioned within the mind of its listener/viewer into new and often shocking constellations. This is the power of the joke, particularly the visual gag. No form of communication can spark within the individual such rapid connections between pieces of information, connections which would otherwise seem incongruous or require slower methods of revelation. It is for this reason that humour, satire, and jokes play such an important role in political communication. That a joke’s power is rooted in its ambivalence and ambiguity, however, makes it theoretically slippery and fundamentally resistant to a consistent or objective analysis that doesn’t take into consideration the incessantly moving social conditions it inhabits.

Nickerson’s joke recalled the litany of half-truths, smears, and attacks on Corbyn and his followers as ‘terrorist sympathisers’ and alluded more specifically to the wreath laying ceremony Corbyn attended in 2014. This ceremony commemorated the scores of innocent victims of an Israeli Airstrike on Tunisia in 1985, but took place near to the graves of those accused of carrying out the 1972 attack at the Munich Olympics. Indeed, the self-proclaimed creator of the photoshop (@timmyvoe on Twitter) claimed in a now deleted tweet that “it’s a satire of him laying a wreath for the terrorists behind the Munich massacre.”

However, visual gags such as these do not work that simply, and this photoshop was primed with the imagery of a particular narrativization of Corbyn that has been years in the making. For example, in addition to the joke’s allusion to the oft-mentioned wreath-laying, it may have sparked recollections of the claim that Corbyn referred to representatives of Hamas as ‘friends’ or conjured fleeting remembrances of Corbyn at the cenotaph and the subsequent media scrutiny of the alleged inadequacy of his genuflection. The flaming car may have recalled in some people ‘The Troubles’ and Corbyn’s position on Irish Republicanism, much criticised by the British Press. Many might interpret this joke as calling Palestinian solidarity into question, or as reaffirming hawkish neo-imperialism.

This joke brought forth fragments of knowledge which remain contested, and others which are unambiguously false. This is why Corbyn felt defamed, and what his supporters begrudged. Corbyn unequivocally did not lay a wreath for these alleged Munich Terrorists, to say as much would be defamatory.

The problem is that people did say this. A lot of people. So often, in fact, so metronomically and so unrepentantly that it has been treated as truth for years without repercussions. The “terrorist sympathiser” jibe was first used by David Cameron in 2015 in a private address to the 1922 committee in a speech made ahead of an upcoming vote on airstrikes in Syria. When Nicky Morgan defended Cameron a few days later on Question Time, she was booed by the audience. Conservative MPs who did not support airstrikes in Syria, such as John Baron, criticised Cameron’s words as inflammatory and insensitive. It is a testament to the British media’s resolve in its commitment to warding off the threat of an anti-imperialist Left populism that the discourse deteriorated so dramatically in only a couple of years.

One would not begrudge Nickerson, perhaps, if his immediate thought upon hearing from Corbyn’s lawyers was, “why me?”

The political reality is that Corbyn could not have challenged jokes like Nickerson’s as leader, or rather he was wise not to. What message would that send? “If you mock me, I will sue you.” How would this succeed in breaking down the barriers between the grassroots and a new political leadership — a tactic that was so crucial to Corbyn’s Left-populism and its messaging? To be clear, I do not begrudge Corbyn in his attempts to protect his legacy — but this case merely signals that what remains of Corbynism is the salvaging of legacies, not the building movements.

The reaction from many on the Left, in their disgust at the initial joke, their celebration at its punishment, and even the calls for more individuals to face legal action, demonstrated an anxiety towards a form of political humour that the Left either participates in themselves or permit when it comes from within their own ranks. But just as importantly, it also allowed for the Right to return to their stereotypical portrayal of the Left as humourless agelasts (non-laughers).

While this might be shocking to those who spend their days scrolling through ‘Left twitter’, it is the Right that has traditionally viewed themselves as being the gatekeepers of humour. In Andrew Neil’s welcome monologue for the newly established GB News, he claimed that the inchoate nationalist news channel would employ “passionate presenters with character, flair, attitude, opinion and yes, a sense of humour.” Across the pond, in his scathing polemic attacking Biden’s withdrawal from Afghanistan, the American pundit and heir-apparent to Trumpism, Tucker Carson, described the Taliban as “primitive people famous for their brutality, rigidity and humourlessness”. It was with shock that the West responded to images of Taliban soldiers enjoying themselves at a fairground. More recently, reports emerged that North Korea banned laughter during the commemoration of Kim Jung-Il’s death, much to the amusement of western commentators (although one wonders how somebody caught laughing at the Queen’s funeral would be treated?)

To portray somebody as humourless has long been a tactic to dismiss ideological positions that challenge an established order, from dismissals of the humourless and/or hysterical feminist to the denigration of the “loony-Left” (a term which although now seemingly ubiquitous, finds its origins in The Economist in the late 70s and became a go-to characterisation of progressives by the mainstream media throughout Thatcherism and the rise of the Militant tendency within labour). To be unwilling to laugh is to be laughable.

It should also be pointed out that satire is just as much of a tool used by the establishment to maintain its grip on power than it is of ‘progressives’ seeking to undermine the established order of things. This can take varying forms, from caricatures of Left figures in explicitly pro-establishment media outlets, to the liberal sneers on programmes like Have I Got News for You. Our political leaders’ corruption, meanness or idiocy is laid bare for all to see, laugh at and then instantly forget once the cameras stop rolling, in either the naïve assumption that such exposure of hypocrisy is sufficient to spark change, or safe in the knowledge that there are enough institutional barriers in place to ensure that such change will not be forthcoming.

Satire can reinforce power just as much as it can undermine it. Some attempt to brook this apparent contradiction through the lazy categorization of that which ‘punches up’ or ‘punches down’, with the former viewed by self-proclaimed progressives as legitimate. But this says nothing of the messiness of power and relies on an implicit hierarchisation of oppression or exploitation which raises more questions than it answers. One quickly becomes bogged down into the unnavigable quagmire of intersectional identifiers such as class, race, gender and so on.

At this juncture, perhaps what is needed in any analysis of political humour is not a check list of permissibility and impermissability, or a list of conditions that need to be met to determine whether a certain joke or gag is verboten, but rather a material analysis of what political humour is, what it aims to do and why? Perhaps the Left should look inwards, assess what has worked and what has not, so that it can formulate new strategies for Left-political humour, rather than gaze longingly at opponents who now have a hegemonic stranglehold over the political, institutional and media power required to ensure they can get away with whatever they like? And perhaps what is needed is a relinquishment of the desire to control the humour of political opponents and instead reassess what it is that Left-political humour has the power to achieve?

It is important to evaluate the recent successes of Left humour. The most effective moments of humour during Corbynism were never strategic, programmatic or deliberate. Rather they were spontaneous responses which included huge masses of people. It is also important to note that these moments often involved Corbyn as the ‘target’, in heavily ironised moments of self-deprecation and incongruity at the prospect of a demographically broad electoral coalition uniting behind the antithesis of a ‘Left-strongman’ in their attempts to depose an unambiguously evil, racist, and violent government which is unafraid of using state violence to repress dissenting voices.

When Theresa May, architect of the hostile environment, infamously claimed that the naughtiest thing she had ever done was “run through fields of wheat”, the moment itself was unambiguously laughable to anybody with any knowledge of the Conservative Party’s history. In the following days, Corbyn was filmed being approached by a group of young people while campaigning and was asked what the naughtiest thing he’s done. He did not mention Theresa May, the Tories, but simply said with a knowing wink “it’s far too naughty to talk about”, to the delight of the group who cheered in response.

This perfectly encapsulated the success of Corbyn’s humour. It was unscripted and genuinely funny. His willingness to engage in spontaneous, unmediated encounters with the general public briefly illuminated the porousness of the barriers separating the public and political that would be key to his populism, which placed the importance of the grassroots, the many, the people, at the front and centre. This sense of inclusivity was vital to the success of the ‘ooh, Jeremy Corbyn’ chant, which captured the dichotomy of people temporarily relinquishing their individuality to unify around a single man, who in turn pledged to bestow power back to them, so that their individual (and social) material needs could achieve political representation.

But this humour emerged after Corbyn’s decades of hard work, toil, and commitment to supporting working class people, marginalised groups and opposing austerity, war, privatisation, and corporate greed. It was precisely this sort of work which had been dismissed as serious, dry and humourless for decades by a neoliberal establishment entirely comfortable with the comedy that lampooned it. Margaret Thatcher was an enormous fan of Spitting Image, and HIGNFY, partly responsible for launching the political career of BJ, encapsulates the cosiness between politics, journalism and a particular form of satire that acts more as a pressure valve than an engine for change.

The Soviet politician, academic and propagandist, Anatoly Lunarcharsky claimed that satire “attains its greatest significance when a newly evolving class creates an ideology considerably more advanced than that of the ruling class, but has not yet developed to the point where it can conquer it. Herein, lies its truly great ability to triumph, its scorn for its adversary and its hidden fear of it. Herein lies its venom, its amazing energy of hate, and quite frequently, its grief, like a black frame around glittering images. Herein lie its contradictions, and its power.” I am sure this will resonate with many on the Left in Britain today.

To be a ‘Corbynite’ was not so much to subscribe to a particular ideology (after all Corbyn has been far more ideologically malleable than many of his critics or followers care to admit). If a ‘Corbynite’ identity did exist, I would suggest that it was a subjectivity that straddled the contradictions mentioned above: namely of grief and hope, solidarity and hatred. Grief for the tens of thousands of people who had died as a result of austerity policies in the preceding five years, for the disabled people targeted by punitive DWP measures, for the millions pushed into poverty. Feelings of hatred and venom for the perpetrators. Hope that for the first time in generations, a politician might stand up and challenge Thatcher’s credo: ‘there is no alternative’ — too often treated as a political truism — the political truism of the past fifty years. Corbynite subjectivity was marked by bursts of frenzied activity and bouts of crippling enervation, doom-scrolling, and inertia. Desperation and despair as the Westminster establishment, fascists, liberals, and actors within his own party coalesced to deny Corbyn’s most fragile of electoral coalitions the change it desperately wanted.

It was from these vicissitudes that an online jargon of Left humour emerged — a language of Left laughter. However, and I say this as a connoisseur and participant, the painful truth is that this laughter sooths defeat more than it builds for future victory. It is more exclusive than it is inclusive and runs anathema to the principles of a Left-populist movement which sought to draw people into its fold. The more successful Left-humour during Corbynism was able to expose universal truths of injustice, not individual acts of hypocrisy. When it relied on incongruous stupidity it drew people together, not pushed them away.

It is perhaps not a surprise that the online-Left’s viciousness has increased following the 2019 election defeat and the tightening of the Right’s grip on the Labour Party, which now appears fixated on the state’s repressive capacities and not its liberatory potential. However, such viciousness has the potential to further exclude swathes of people, now tired of a decade of austerity, the coronavirus pandemic, rising bills and falling living standards.

This is not to say that the Left should lose its sense of humour. But perhaps we should instead follow Corbyn’s example and put in the hard work first, and hope that when the next opportunity arises, the humour that emerges will help to push us over the line.